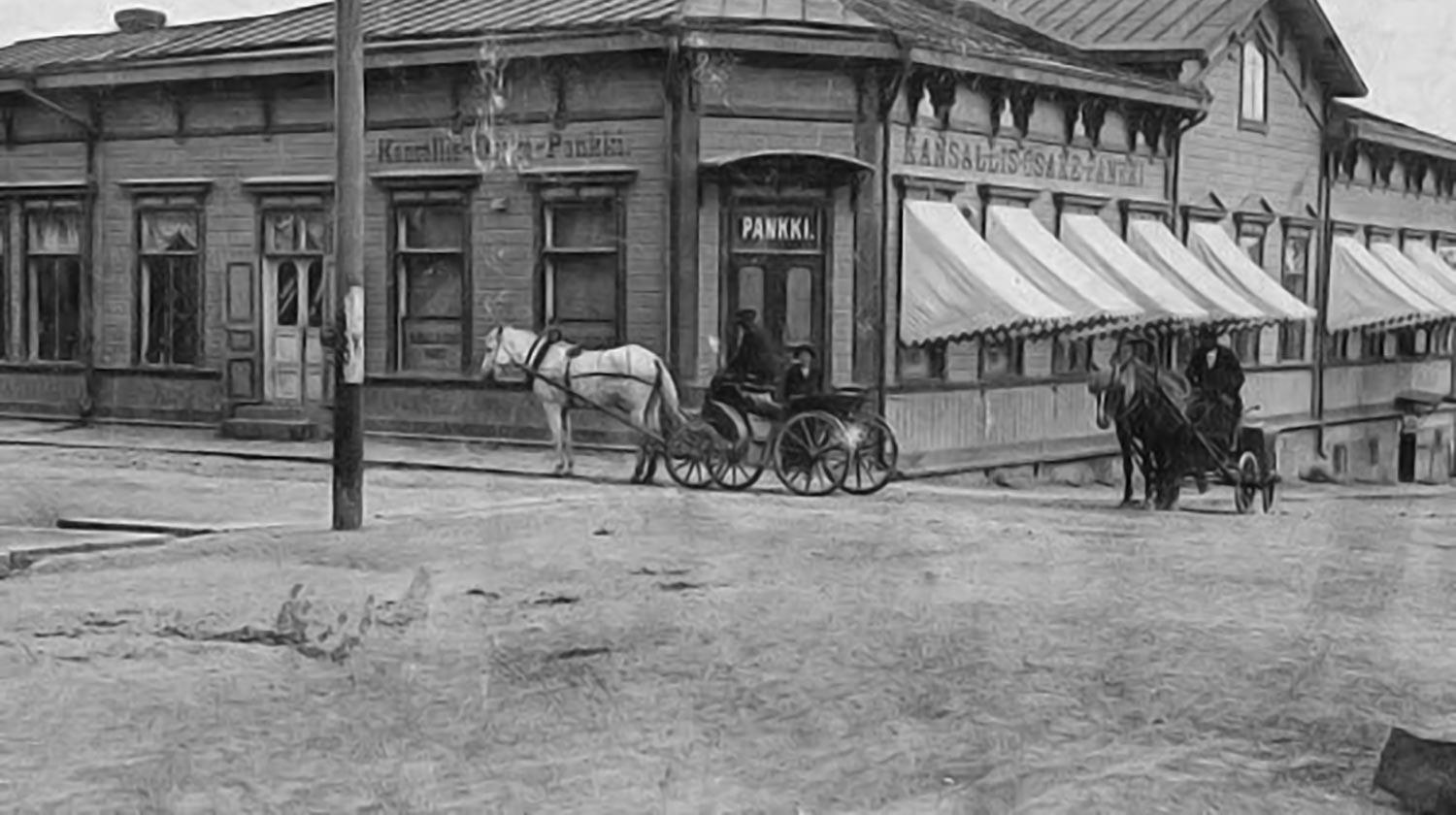

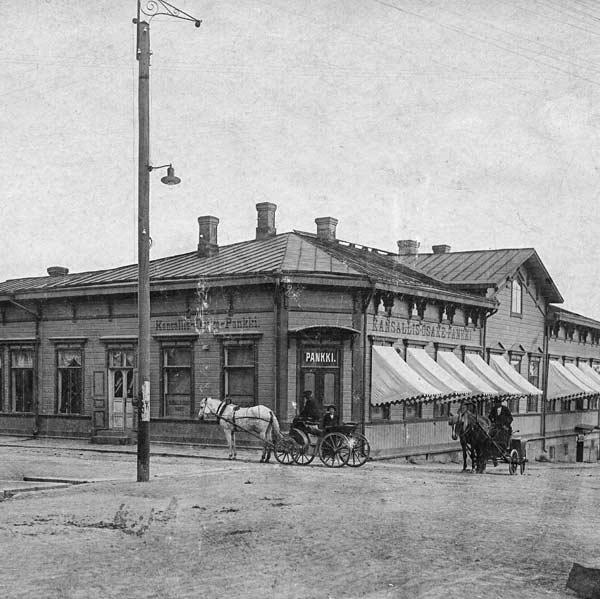

A city in a village

The city of Jyväskylä was founded in 1837 between Harju and Jyväsjärvi. They key reason the city was founded was to support market life in the area. Commerce and livelihoods were strictly restricted in Finland until the early decades of the 19th century, and trade was only permitted in cities.

The parish of Jyväskylä had already been a great marketplace and crossroads before it became a city, so there was good reason to develop the area. The region’s good waterways and access routes, its central location, forests, lush agricultural land and the belief that the land was rich in iron ore all added momentum to the idea of founding the city, which had been proposed on and off since the 18th century.

Jyväskylä’s beginnings were rather modest. The state newspaper Suometar ran a story around 15 years after the city was founded, stating: “Jyväskylä! Is it really a city?” Nevertheless, Jyväskylä and its grid layout differed greatly from the earlier village, which was only intersected by a single main road.